Stitch Direction in Embroidery

Articles offering general knowledge of stitch direction, which was (and still is) a common question among embroiderers, were welcomed by Victorian ladies. They understood that proper stitch placement was essential to make their embroidered pieces look natural as well as beautiful.

Many magazines of the era published information on this topic but the following article was one of the first, and probably one of the most copied articles of its time. It ran for many years, without change, in many of the Corticelli Home Needlework magazines, which was published by the Florence Publishing Company as well as Lessons in Embroidery published by Brainerd & Armstrong.

The article below was written and copyrighted by MRS. L. BARTON WILSON and published in Corticelli Home Needlework in 1899. It has been edited for use on this site.

The Principle of Stitch Direction

The “direction“ of stitches in the kinds of needlework which we consider purely mechanical is evident, and in many cases, optional. This is by no means the case in the embroidery which we recognize as the culmination of the art, that which has a certain freedom and spontaneity and is therefore more artistic than any other sort. This seeks to express nature, within a certain limit, and its stitch direction is governed by a principle which has its foundation in nature.

It is a very interesting ground of action and very beautiful in its demonstration, as all scientific principles must be.

The “Feather stitch,” or “Opus Plumarium, “sometimes wrongly called the “Kensington stitch”, and necessarily the element of which it is composed and which we have come to know as the “Simple Long and Short stitch,” are frequently spoken of as “the embroidery stitches,” as though there were no others worthy of the name. They are certainly the most perfect and scientific method of the art. This paper treats of the direction of these stitches as applied to natural forms. The application of this “stitch direction” to the conventional is only carrying the matter a step farther, in which case it must be determined by the relation of the conventional to the natural, from which it is derived.

Whenever we find ourselves doing anything several times the same way we begin to realize that it alone is the right way and it is at once safe to conclude that a principle is therein involved which may be discovered, analyzed, and formulated. The history of art, and of all other work, proves that the right way of doing things is usually “felt” by those who, as we say, have a certain “natural insight” or “gift.” These individuals work along the lines of principle unconsciously, and when their work has become the standard the principles are formulated from it for the benefit of those who follow the originators.

We therefore naturally come to the conclusion from the study of the old embroideries and from the fact that modern schools of art are founded upon this work, and are following after it, that there is a needlework method based upon principles by means of which the questions of learners may be satisfactorily answered.

The most important questions which arise in the mind of the embroiderer when she attempts work which is something more than mechanical is that of the slant or “direction” stitches should take. A most satisfactory answer applicable to our nature designs is this: “The stitches should take the same direction as do the lines of texture in the flowers and leaves.” But then we must be more explicit than this, for we know we can go behind that which is apparent and discover the line of principle along which nature works. Until we find it in this case the application is limited and we are forced to prove each instance by examining the natural forms. We want rather to be able to define reasons, capable of ready proof, which will remove one of the chief difficulties to amateur work.

We find that we can do this by considering every form whether composed of curved or straight lines in its relation to a circle constructed on the center-of-radiation of the form.

It is perfectly evident that the stitches in “Opus Plumarium” and the simple rows of “Long and Short” stitch are radiating. Having perceived that they radiate and at the same time bear a regular relation to each other we conclude that they have a common center and we have only to find this center and construct the circle to see that the stitch direction coincides with the radii of the circle.

The base of a flower or leaf is the point of attachment between it and its stem, and this is its center-of-radiation. Set one arm of the compass upon this point and construct a circle which shall contain the form, draw its radii, and the mathematically correct direction of every stitch will at once be apparent.

We find three classes of forms: first, the single leaf or form composed of one element, Fig. 1; second, the form composed of groups of simple radiating elements, Fig. 2; and, third, the form composed of two or more elements related but not by a common center, Fig. 3.

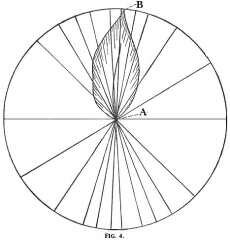

Fig. 4 demonstrates the principle as applied to the simple leaf form. The base of the leaf, “A,” is the center of the circle which we wish to construct. The apex of the leaf, “B,” we choose as a point on the circumference because it is farther from the center than any other point contained in the form, therefore a circumference containing this point will include the entire form. The correct stitch direction is indicated in the illustration and it is clearly one which coincides with the radii.

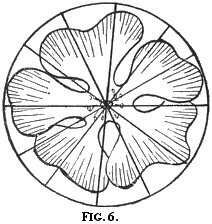

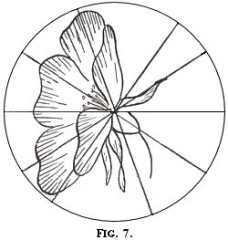

Fig. 5 shows a very common mistake and we can very easily see why it is a mistake. Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 are the natural result of carrying out the principle relative to the second form, the one composed of a group of simple forms radiating from one center.

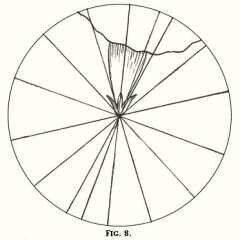

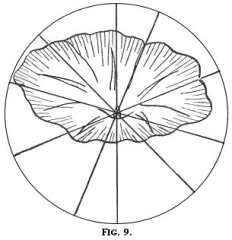

Figs. 8 and 9 show our principle applied in the third case to the constituent parts of the morning-glory blossom. The base of the tube is easily discovered and on it as a center we may construct our circle with its radii and so find the stitch direction. Fig. 18. When we consider the flaring corolla alone we find its point of radiation by "producing" the stem to the point where it would be attached if the flower had no tube. Then we may proceed to apply our rule. Fig. 9.

Fig. 10 shows a variation in what we should be likely to consider a simple form but which because of the position of its center includes nearly all the radii of a circle. This morning-glory leaf is a very pretty proof of the principle.

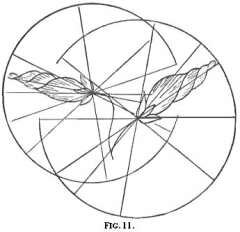

Fig. 11 shows another kind of grouping with one center. The morning-glory bud thus worked pretty twisted effect as in nature.

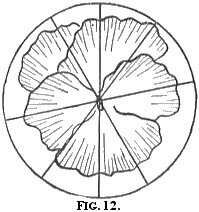

Fig. 12 gives the pansy stitch direction.

Thus nature works always within the bounds of principle. If we take this rule back to nature we shall find it almost invariably verified in the texture and veining of leaves and flower petals. The comparatively small class of parallel veined vegetation is the largest exception, but no question of stitch direction arises in this case. Flowers of unusual form may present a seemingly individual difficulty as to the slant of stitches but a little study of the specimen will surely reveal an especial application to the rule.

If we seek answers to our questions from nature we will find them in most simple language. No elaborate or labored explanations are necessary when we have the key.

The Last and Best Book of Art Needlework

Over 100 pages of authentic Victorian instructions and patterns from 1895!

FREE

Beeton's Book Of Needlework

433 pages!

Sign up for VEAC! Everything you wanted to know about Victorian embroidery, needlework, crafts and more!

Priscilla Bead Work Book

Make Beautiful Victorian Beaded Purses, Jewelry & Accessories - Starting

TODAY!